The Everlasting Light Bulb

Take a drive to Livermore, California and what you find may surprise you. In a corner of Fire Station No.6 lies something called a Centennial light bulb—the longest continuous light bulb in the world. It's been on for 120 years since 1901 and it’s not even connected to a light switch. Designed in France and made in Ohio, the glass was hand blown not long after commercial lightbulbs were first invented. It has been burning for over a million hours.

Sadly, it turns out that everlasting lightbulbs are a bad business model. Once everyone has one, you can't sell more. You can only sell repair services. And that's exactly what used to happen - light bulbs used to last for much longer, and electric companies used to install, maintain, and replace the bulbs to make more money.

Traditional light bulbs were really heat bulbs with a byproduct of light. The filament in a bulb needs to be extremely hot to generate enough light, so 95% of the energy was wasted as heat. Edison's first bulb had a cotton filament which lasted for 14 hours. As people iterated on the idea the filament material changed from carbon to tungsten, which was 8 times smaller. The lifetime of bulbs grew dramatically as a result, until around the 1920s. By this point lightbulbs already lasted 2000-2500 hours.

As bulb lifetimes grew, company profits shrank, until eventually, light bulb manufacturers had to step in.

The Great Light Bulb Conspiracy

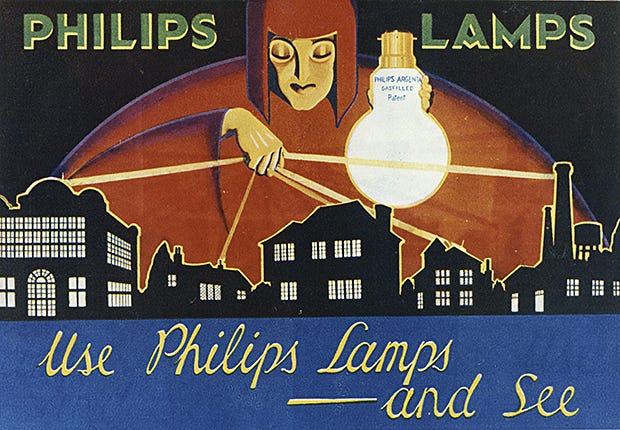

In Geneva, Switzerland there was a secret meeting of top executives from the world's leading lightbulb companies, including Phillips, International Electric, Tokyo Electric, Osram (Germany), and Associated Electric (UK). These companies formed the Phoebus cartel, named after Phoebus, the Greek God of light.

These companies committed to supporting each other by controlling the global supply of lightbulbs. Smaller manufacturers had been swallowed up and consolidated, and their only remaining threat was the lifespan of lightbulbs. In 1933 Osram sold over 60 million lightbulbs, but the following year, they only sold 28 million.

The companies agreed to reduce lightbulb life spans to just 1000 hours, cutting the existing average in half. They would send lightbulb samples in for testing, and for any bulb lasting longer than 2000 hours, the company was fined. There are records of these fines being issued to companies for every 1000 bulbs manufactured. This was also how they developed a global standard for light bulb screw threads.

So now the engineers needed to innovate to decrease lifespans, testing different designs and filaments to make shorter and shorter life lightbulbs. None of this was done with consumers in mind. It was done to make money.

By 1934, just two years later, the average bulb lifespan was around 1200 hours. Bulb life was cut in half and sales increased by 25%.

The cartel eventually broke apart due to the outbreak of World War Two, but their practices lived on in what became known as planned obsolescence.

Manufactured Change

The first time planned obsolescence was used in print was a 1932 pamphlet by a real estate broker named Bernard London. It was a plan for ending the depression by mandating that products should include artificial expiration dates after which people would have to pay a tax for hanging onto and using old things.

That idea didn’t take off but later that year a book was released by Roy Sheldon and Egmont Arens called Consumer Engineering: A New Technique for Prosperity. They called it creative waste. The hypothesis was essentially: 'we should make things less so people will buy more stuff'.

American designer Brook Stephens defined planned obsolescence as:

‘instilling in the buyer the desire to own something a little newer, a little better, a little sooner than is necessary’.

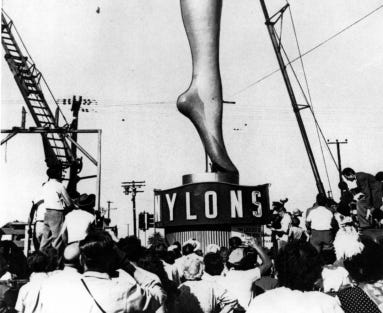

When Nylon replaced silk in women's stockings, everyone wanted to get their hands on the longer-lasting fabric. Riots broke out as a result. When manufacturers realised the product was too good and too hard-wearing, they had to make a change. They couldn't destroy it, so they instructed engineers to find ways to weaken it and shorten its lifespan, following the Phoebus cartel blueprint.

Dynamic Obsolescence

This evolution in manufacturing is best exemplified by two quotes from the automotive industry.

In 1908 Henry Ford released the Model T as the first mass-market car. He envisioned it as a workhorse - an affordable tool that wouldn't wear out. Ford said:

‘We cannot conceive how to serve the customer unless we make for him something that, so far as we can provide, will last forever. […] It does not please us to have a buyer’s car wear out or become obsolete. We want the man who buys one of our cars never to have to buy another. We never make an improvement that renders any previous model obsolete.’ — Henry Ford, 1922

But by 1920, 65% of American households already owned a car. Not long after, during a small economic downturn the sales for both Ford and General Motors took a hit. Nobody needed a new car when the one you owned worked just fine - and everyone who could afford a car already owned one.

The next year, Dupont, a paint company, took over a controlling share in General Motors and started an experiment painting cars in different colours to drive up demand. In their own words, the aim wasn't just to make other cars feel outdated, as all Ford's were black, but to make their own cars feel outdated. They pushed out a new colour of the same car each year. Everyone clamoured for the new one, and planned obsolescence morphed into modern consumerism. GM's head of design called this 'dynamic obsolescence'.

"Our big job is to hasten obsolescence. In 1934 the average car ownership span was 5 years. Now [1955] it is 2 years. When it is one year, we will have a perfect score." - Harley Earl, head of design GM

Apple has achieved that perfect score. They’ve mastered dynamic obsolescence, delivering slightly updated designs and slightly different colours of their products each year. Every few years they can take a leap forward. In the interim, they can take features that already exist, polish them, and market them as innovations.

The company became embroiled in controversy when people realised that old phones would start getting slower as new ones were released. And when there were issues, the cost of repairs was so prohibitively expensive that you may as well buy a new device. Apple said they were slowing down devices to stop the batteries degrading, but the only reason they needed to do that was because they had designed the phones so consumers couldn’t replace the batteries themselves.

None of that was accidental. Apple controlled the products after purchase in a way that meant you could only take them to Apple for repairs if you wanted to keep your warranty. Apple had to pay hundreds of millions of dollars in court as a result of these practices, but they can afford it - they have a war chest of cash specifically devoted to court cases like that.

The Socialised Obsolescence of Happiness

Dynamic obsolescence is all around us. In fast fashion, it's implemented through designs that only last one season. Every season the clothes are swapped out. Fashion houses like Burberry have even been caught burning old stock to prevent it being resold.

There's a constant push towards more and marginally better. When you run out of innovation you do throwbacks.

We bring back shapes and patterns from the 70's, 80's, and 90's. Film franchises get resurrected with new casts and directors. The iPhone 11 looks like the iPhone 4. We go backwards to go forwards. Everything is recycled to extract a little bit more money, and consumers don't complain, we love it! Keeping up with the Joneses allows us to elevate our status and be part of the in-group.

So now printer cartridges have chips inside. Some chips prevent you from using any ink that wasn’t supplied by the manufacturer. They also tell the printer when to stop using ink - not when it runs out - just when it reaches a pre-determined amount which would prompt you to go buy more.

Car companies discontinue parts and retire old popular models in order to drive sales of the new ones. Another big racket is college textbooks with new editions where they just change page numbers. Non-fiction books become intentionally bloated and contain fewer ideas so publishers can sell more in a series. Toy companies enforce a system of something called contrived durability, where they make moving parts more flimsy.

Eventually, it has become consumers that drive the cycle of fake innovation. People want new things faster than companies can make meaningful updates, so they are now incentivised to sell iterations and fancy colours. According to a report by the Ugo Institute, a third of replacement purchases of home appliances was driven by people simply wanting a newer unit rather than due to faults. Similarly, by 2012 over 60% of replaced TVs were still functioning.

People use phrases like ‘military-grade’ as a synonym for durability. All it means is they're making things durable the way everyone used to, but the only people who still do that are the military.

This is what I'm calling the socialised obsolescence of happiness. By prioritising status and newness we're making satisfaction and contentment obsolete. Even among those wanting to shop and live sustainably, all it has birthed is a brand new industry of identical products in washed-out neutral tones, where people buy just as much but feel better because the label says 'organic'.

Productive Obsolescence

If you made it through the stories above, you should now be much better informed about the way manufacturers drive your shopping habits. I'll leave it up to you if you want to adjust your consumption as a result. Instead, I have some prompts about how we can intentionally utilise obsolescence in our personal lives.

Many of us already practise planned obsolescence without realising it. Planned obsolescence is the cheaper pair of jeans you buy while saving up for the pair you really want. It's doing this degree or taking that job until you figure out what you really want to do. It's settling for a relationship because 'this is the best guy I can find right now’.

Often our internalised obsolescence is unintentional and unproductive. Your stop-gap job ripens into a miserable career. The relationship you settled for causes one or both of you pain and missed opportunities. The cheap jeans you bought get torn and thrown away.

Here are a few suggestions on how to make obsolescence work for you:

- Learning - Aim to learn enough each year that your past selves seem foolish. Increase the velocity at which you encounter new and better ideas. Increase the variety of ideas you consider. Read books from other domains. Learn skills outside your wheelhouse.

- Thinking - Borrow ideas and opinions rather than adopting them. Make the old ones obsolete. When you come across something new and convincing, tell yourself you're only going to agree until a better idea comes along. Stress-test the weak points in any argument. Avoid entrenched ideas and politicised beliefs.

- Business - Think about how you can design systems that will reduce your day to day involvement. What can be automated? Where can you delegate? Design your availability and your solutions to help people solve their own problems. Use text expanders, keyboard shortcuts, and any tool that marginally cuts down the time it takes you to be productive.

- Habits - Think about what habits you can build that can bridge the gap between your present and ideal behaviour? What's the smallest possible domino? Similarly, think of what obstacles you can create to impede the behaviour you want to change. If you want to be healthier, take a longer route to the store. Hide the bag of snacks at the back of the cupboard. Move the sweets to the top shelf. Make what was once appealing less accessible, so the apple on the counter seems more attractive.

- Living - make better plans, and think further in advance. Give better gifts to your future self, and engage in activities with compounding returns. Make yourself indispensable to friends and loved ones. Contemplate your decisions and actions, making yourself 1% better each day.

React to this issue by clicking an emoji: 😍 | 🤯 | 👍 | 😴 | 👎 | 😡

If you have any thoughts on obsolescence, productivity and waste I’d love to hear from you! Reply via email, leave a comment, or send me a tweet!

I’d also love any thoughts on what I should write about next.

Read on for this week’s recommendations >>

Reading list

Books I’ve read/seen/will impulsively buy and add to my “to read” shelf on Goodreads. Recommendations from newsletter readers are always welcome:

- Several Short Sentences about Writing by Verlyn Klinkenborg - wishlisted. A book recommended by one of my favourite creators, Austin Kleon. A reference book about the act of writing, what we notice, and what we don’t.

- Designing the Mind by Ryan A Bush - impulsively bought. This book is about neuropsychology and how we can reprogram our minds for better outcomes.

- Surely You're Joking Mr Feynman by Ralph Leighton - seen. Feynman was one of history’s greatest theoretical physicists and had a knack for teaching the complex in simple ways. This book has a collection of anecdotes about the endlessly curious Nobel Prize winner.

To win a book from the reading list backlog, check this space next time.

Let me know if you have any book, film or resource suggestions for next week. Feedback is welcome too! Email me or drop me a tweet here. Until next time!!